George Vasey on Ben Cove in SPACE

Ben Cove’s (1974 – 2016) work is promiscuous, involving itself in a polyamorous play with a wide range of ideas, objects, and themes. During his career, Ben had dalliances with Berthold Lubetkin, affairs with De Stijl and long-distance correspondence with Memphis design. Ben’s interests were a broad church: art (all kinds), interior design, the Afrofuturism of Sun Ra, urban planning, architecture, computer graphics, and museology. You name it, Ben read about it. While thematically and formally diverse, his work remained resolutely singular, unwaveringly Ben Cove’s.

I write this opening paragraph smiling and wondering what Ben would make of my curious metaphors. I worked with Ben several times early in my career, curating him into exhibitions and writing on his work. He once even designed a website for me, one of his many side hustles. Revisiting our collaborations and reading my texts on his work evokes the richness of our conversations. Ben’s precocious curiosity was unlimited.

In the book Curious Minds: The Power of Connection, 2022, Perry Zurn and Dani S Bassett explore the concept of curiosity. It’s a book that Ben would have greatly enjoyed. Zurn and Bassett outline various types of curious people. The authors explain that hunters are deep divers, dedicating their expertise to a specific focus; and then there is the figure of the busybody:

“Busybodying can function as an act of radical listening – one that enrols the curious person in the project of a dialogical experience, living through…all the other curious beings and things in the world. It is more likely to stretch beyond traditions, canons, and dominant knowledge systems to hear what often goes missing or falls through the cracks of the prevalent social logics.” (Zurn, P & Bassett, Dani S, 2022, Curious Minds: The Power of Connection, MIT Press)

Busybodying curiosity dismantles as it connects and disrupts through constructing. Ben was the archetypal busybody and his curiosity generated imaginative trajectories across fields of knowledge. His boundless work operated as a connective tissue between modes of being, doing and thinking. Promiscuous busybodying: that was Ben’s method and material.

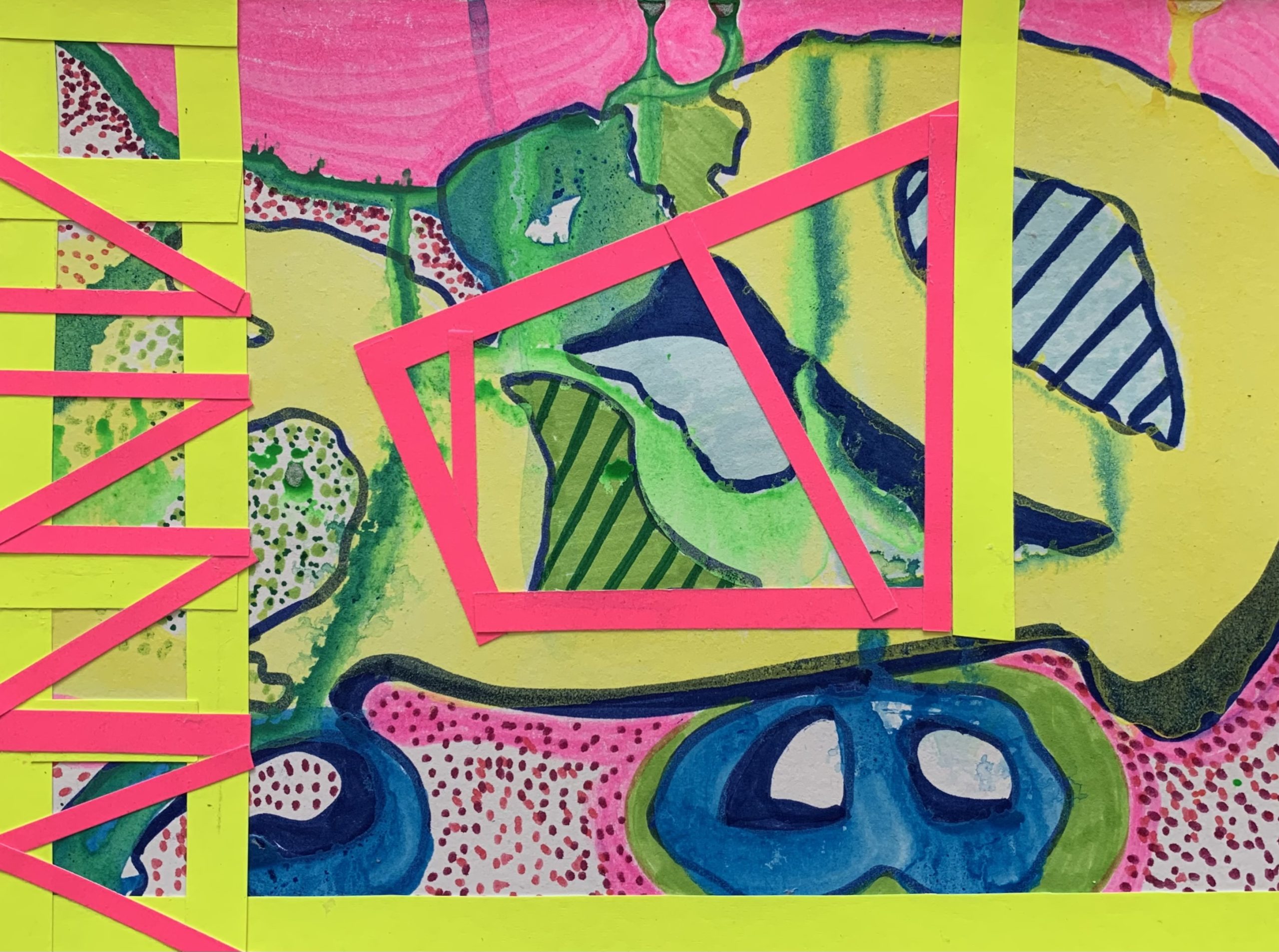

Ben’s work also evaded language and, as such, was always fun to write on. Take the painting Freeloader, 2014, which is typical of his later practice. It looks like something turning into something else, biomorphic objects that appear fragmented and hallucinatory. Like all of Ben’s canvases, it appears animated and agitated.

A square canvas is framed on three sides with trompe l’oeil cornice. This frame is partially obscured by two curvilinear abstract shapes in the middle of the image. In raking light, the underlayers of acrylic paint peer through, evidencing the reworking over time. The paint application is varied; stippling, washes, and shading while other parts are matte and opaque. The light source is often multi-dimensional as is the perspective which veers between isometric and one-point perspective. Some forms are fleshed out while others are flattened. Ben was fond of the tensions that paint could create. The work betrays Ben’s initial education and persistent interest in buildings and facia; the imagery encompassing a broad range of architectural vernacular.

We can draw genealogies between Ben’s work and painters such as Tomma Abts and Charline Von Heyl. Each artist twists traditional abstraction, sharing a trickster sensibility. Paintings veer off in unexpected directions, tripping us up as we make our way around the canvas. Ben referred to his process of painting as a form of “looking out of the corner of my eye”. He rarely painted from sketches and preferred to work up a canvas intuitively, revising as he went. This indirect looking carries with it errancies that are isolated and amplified in the resultant images. Errant formalism, unruly futurism, trickster abstractionism; this is a type of art that seems to call out for a new type of painterly-ism.

Another painting in the series, Interloper, 2014, continues these thematic and formal tropes with a more acidic and high-key palette of yellows, oranges and pinks. Here the biomorphic shapes are broken up by a grid. The painting merges municipal and rococo imagery, and, like much of his work, it is redolent of a certain strand of Post-Modern architecture. Growing up in the Seventies and Eighties, this is the imagery of Ben’s youth, and he was equally at home in the world of kitsch Neo-Classicism as he was with austere Minimalism.

The influence of architecture is most keenly felt in an earlier body of work: the Regular Work series, 2008, which features enigmatic forms situated in the middle of modestly scaled canvases. These forms read as hypothetical pavilions or follies. Painted quickly, they offer an intimacy that contain a kernel that Ben goes on to expand in his later works.

Typical of Ben’s later practice, he would often convene paintings atop large black and white photographs, sometimes installed on discreet modular shelving units. Biker Gang Hideout, 2016, portrays the aftermath of what looks like a party, the picture partially obscured by the paintings. Police Scuffle, 2016, depicts a mid-Sixties image of police violently detaining someone. Ben’s abstracted vernacular looks estranged amid the directness of the documentary photography. Who are these people? Where are we? Where are the images sourced? Ben leaves the images deliberately ambiguous lending further cognitive dissonance.

The work can be read in different ways. The photograph amplifies the optical qualities of the painting. The canvases are signal and noise, directing us to the image underneath while simultaneously obscuring it. By forcing a confrontation between two seemingly opposite strategies – abstraction and documentary – Ben unbalances the neutrality of the gallery and his own paintings. Furthermore, he seems to suggest that painting, in its own way, carries a documentary impulse, a record of actions and intentions not dissimilar to the photograph.

Writing about an artist I knew, after his passing, creates certain tensions. The world moves around the work generating fresh resonance. You feel a particular responsibility to honour the conversations as much as the work itself. It’s paramount that the work continues to grow, freed from the constraints of the artist’s intentions.

An element of Ben’s life feels significant to mention and yet, it only came up in our conversation once and I didn’t refer to it in my previously published writing on the work. Ben had Osteogenesis Imperfecta, more commonly known as Brittle Bones. In a wheelchair since birth, Ben navigated the world from a specific vantage point. In our conversations, Ben was quite specific in not wanting his later work to be read through the lens of his disability. He moved through a body of earlier work that had more overt reflections on his disability, and this symbolism receded over time as his vocabulary diversified into abstraction.

These early paintings were often large in form. Flat colour was applied whilst they were laid on the floor, and the subject painted after Ben heaved the canvas upright using a pulley system that required wheels on the base. These were then displayed leaning against the wall, the wheels, integral to the making, were left on. Favoured subjects included Superman, space travel and astronauts, often partially obscured and framed by large expanses of blank, brightly coloured space. The process of Ben working on these paintings is captured in the Channel 4 documentary Natural Born Talent, 2002, by Malcolm Venville.

In reflecting on Ben’s practice, it feels important to say that, while his disability informed his entire practice, his later work was more covert in its politics. Ben wanted his work to be ambiguous, sly, complex, poetic, beautiful, and difficult; he didn’t want it to be seen through a specific lens. In looking at these later paintings, we see someone engaging with the built environment and fabulising a world unlike this one. From the transportive poetics of outer space to the radical potential of Afrofuturism, Ben was interested in what was possible as much as what already existed. His work is infused with this mindset. Perhaps, growing up disabled in late 20th century Britain, it’s understandable that the moon was more compelling than Manchester.

The title of the exhibition, Ben Cove in SPACE, summarises it well. SPACE is an organisation where Ben spent many years working. Space is somewhere else. It’s a place of potential where the typical rules don’t apply. Upside down can be the right way to be. There is no horizon line in space, only vast boundless potential. Most of space is made up of dark matter which makes up much of what is around us. We have no sense of it and have yet to evidence it. Physicists believe that we can only sense about 4% of what is around us. Our bodies and their sensing organs are extremely limited in their scope. While we need science to help us prove the presence of dark matter, we also need artists to tell us why it matters. Art can illuminate the darkness with metaphor and melody. We need more artists like Ben Cove, with their busybodying curiosity, able to help us sense that other 96%.

An old tutor of mine, the art historian Francis Spalding, once said that curiosity was like a kiss that could bring an object back to life. Curiosity as a form of resuscitation, bringing ideas and objects from the dark into the light. If Ben’s curiosity was a kiss, it was a full-on snog rather than a peck on the cheek.

George Vasey is a Curator and Writer based in Saltburn by the Sea.