Sophie Collins on Regrets, I’ve Had a Few

Structures of Desire

I first met Lindsey – henceforth L – on a rainy Tuesday morning, in her temporary studio in Ilford. We spoke about her practice in general and about this show in particular. We spoke about her collaborators, the group of people she was teaching to make. We spoke about regrets and relationships, about art, labour and creativity. What follows is an indirect account of that conversation, as well as a semi-sincere attempt to self-advise.

Advice should always be given in the second person –

—

‘Do not be charmed by the long arch of your own trajectory

but shoot along boldly on the hard gaze of the straight

…

put yourself on the margins but don’t be endlessly naming them

…

in any event you will need music

remembering not to think yourself happy until you are

which you will know

then go for it’

– ‘The ambition to advise speaks’, Denise Riley

Advice is an uncountable noun. Like (broken) china or (spilt) milk, it cannot be made plural; there is no unit. There are parameters but their edges are tenuous, surpassing what the eye can see.

Advice outruns the physical, is tentacular, endless: no wonder we encounter so much of it.

/

A proverb might be at once as personal and impassive as colour.

For months you waged a battle against the figurative, calling it misleading. Calling it regulatory; the language of metaphor seemed to you restrictive, offering formulas through which to process what were, in reality, far more complex experiences.

Now you wonder what the harm is, exactly, in drawing comparisons, in calling on cliché. Clichés offer comfort, humour, a shared language. In retelling our stories, their use might ease fear of judgement, the heightened pressure levied by original expression. A proverb is a salve, too: a way of presenting the past as a lesson learned, of staking a claim to experiential knowledge, something which can – to some extent – qualify the pain lived and relived.

Still you find the most effective offerings to be those that get straight to the point, imparting largely practical advice. L cites Mary Schmich: ‘Be kind to your knees, you’ll miss them when they’re gone.’ And to your younger self you wish to say, quite simply, ‘Look after your skin.’

/

‘I’m not going to make this easy for you,’ he said one morning, bearing down. But in a few short weeks you were on your own again, in a flat that made you feel as though you were living on the dashboard of a car. A friend who found herself similarly displaced opted for a mezzanine apartment, which, decked out in a geometric, monochromatic scheme, gave her the impression of being inside a chess piece.

The view from here is of a quiet, moneyed crescent. The buildings are sandstone, their slate-tiled roofs bound by ornate iron railings. The couple opposite have flanked their main-door flat with outsize ceramic vases of differing heights, which snags your gaze each time you look. Perhaps they enjoy the asymmetry.

/

The act of falling in love always begins with a case of mistaken identity, which is to say, of projection. Constellated facts form a personality that in retrospect is so willed (on your part) as to make you feel genuinely alarmed at the thought of having cohabited with a relative stranger. He saw you sleeping. He minced around your pain. No one deceived you; you deceived yourself. Hindsight is 20/20.

You notice that you are taken with artworks that prompt you to illusion yourself, the Renaissance Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s portraits being just one example. In Four Seasons, a series in which masculine portrait heads are made up of the spoils of spring, summer, autumn, winter, the artist asks us to mistake a match for a tongue, firesteels for a nose or ear, a heap of grisly ocean fish for an entire man’s head. He asks us to not only acknowledge but to admire the illusion.

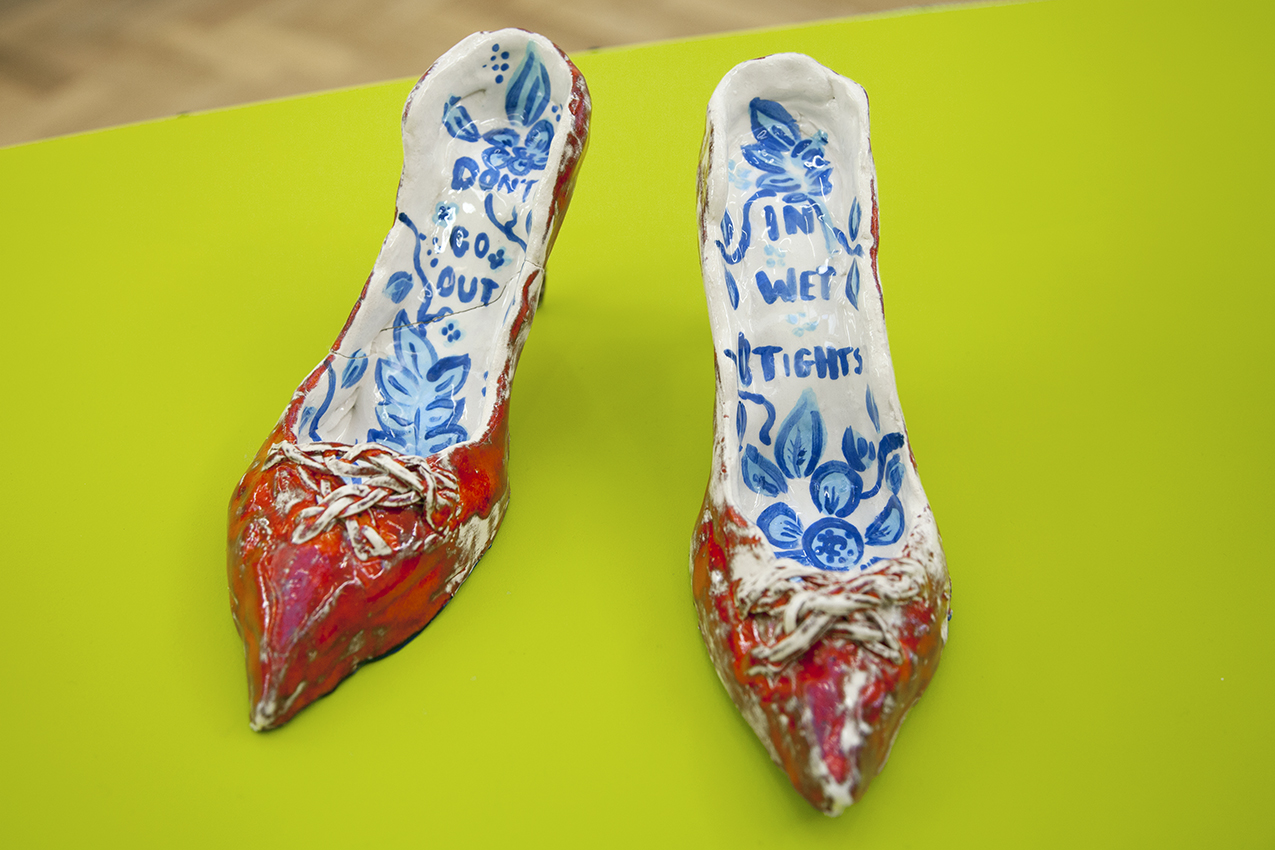

In earlier work, L’s men are similarly reduced to their material conditions, are mottled torsos and desert boots, artefacts at once primed with glaze and physically degraded, lacking, in parts, definition and proper structural integrity.

/

In folklore, deception is par for the course. In Flemish art of the sixteenth century the necessary hoodwinking involved in (feminine) infidelity is well-represented (male indiscretion, less so). As such, there was a common expression used: ‘She’s putting the blue cloak on her husband.’ In Breughel’s Netherlandish Proverbs, the cuckold is at the centre of the painting. His wife tenders him the blue cloak, though his gestures – a feeble hand grasping at the hem – suggest a degree of complicity.

L’s cloaks, however, are not tools of obfuscation; rather, they are signals of recognition and warmth, material demonstrations of empathy. They are elaborations, lending the memories of others increased weight and credibility.

/

‘You want to feel held,’ the therapist said. ‘Figuratively. Emotionally. We might use the analogy of the hall light left on for the child who is afraid of the dark.’

Of the garment offered without prompting, which, in addition to its practical benefits, represents a tacit acknowledgement of the other’s needs.

/

Narrative is a structure of desire. To offer advice is to narrativise, retroactively, one’s own life. But memories, most of us are ready to admit, are vulnerable, the paltriness of our recall disturbing. A memory is a coiled effigy to will, an imprint of an event whose very occurrence might be contested.

Episodes of rampant nostalgia leave you feeling sick and sticky, coated in ectoplasm: the rabid feeling of consenting non-consent, of objections caught in the throat and mind; florid mould along the living room skirting; a crescent on the wall where a glass impacted it squarely. But this, now, is a room where things are made not destroyed, where developing structures breathe lightly under thin sheets of hazy plastic, alien loaves. You feed them drops of rose oil on winter afternoons and begin to fall in love again, slowly and suddenly, deeply and against your own good advice, which you have never been wont to follow.

Everything is strange again now and better for it.

--

Sophie Collins grew up in Bergen, North Holland, and now lives in Glasgow. She is the author of Who Is Mary Sue? (Faber, 2018) and small white monkeys (Book Works, 2017), and editor of Currently & Emotion (Test Centre, 2016), an anthology of contemporary poetry translations. Her translation from the Dutch of Lieke Marsman, The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes (Pavilion, 2019), was published earlier this year. She is a lecturer at the University of Glasgow.

Lindsey Mendick: Regrets, I’ve Had a Few

Artist Lindsey Mendick talks about Regrets, I’ve Had a Few

Curator Tour: Regrets, I’ve Had a Few

Grand Opening of SPACE Ilford

Making SPACE for art in Ilford

Anna Chrystal Stephens: Anorak

Anna Chrystal Stephens: The Making of Anorak