James Smalls on ♪ Here is a Strange and Bitter Crop ♪♪

In a thought-provoking way bordering on the philosophical, Soufiane Ababri’s artistic practice candidly grapples with societal dysfunction while remaining accessible to a general audience. As a result, his works invite a variety of interpretations. He prefers drawings that may come across as stylistically naive and crude, but that manage to retain sophisticated messages around issues of ethnicity, masculinity, gender and homosexuality. With his current and past work, the artist is interested in how the role of dominance penetrates and contaminates the history of representation. The simplicity of these images manage to rebuke and subvert hierarchies of repression and control. As such, the content and formal means of expression become highly political and socially engaged in promoting visibility to the ethnically and sexually oppressed. Ababri has confessed that the end goal of his drawing style and chosen subject matter is “to dismantle the mechanisms of domination and to thwart oppressive social dynamics and power relationships at play.” That objective can be seen throughout the present exhibition, ♪ Here is a Strange and Bitter Crop ♪♪, as well as in a new series of drawings Beautiful Fruit based on an array of pictorial and social references that reveal themselves eventually.

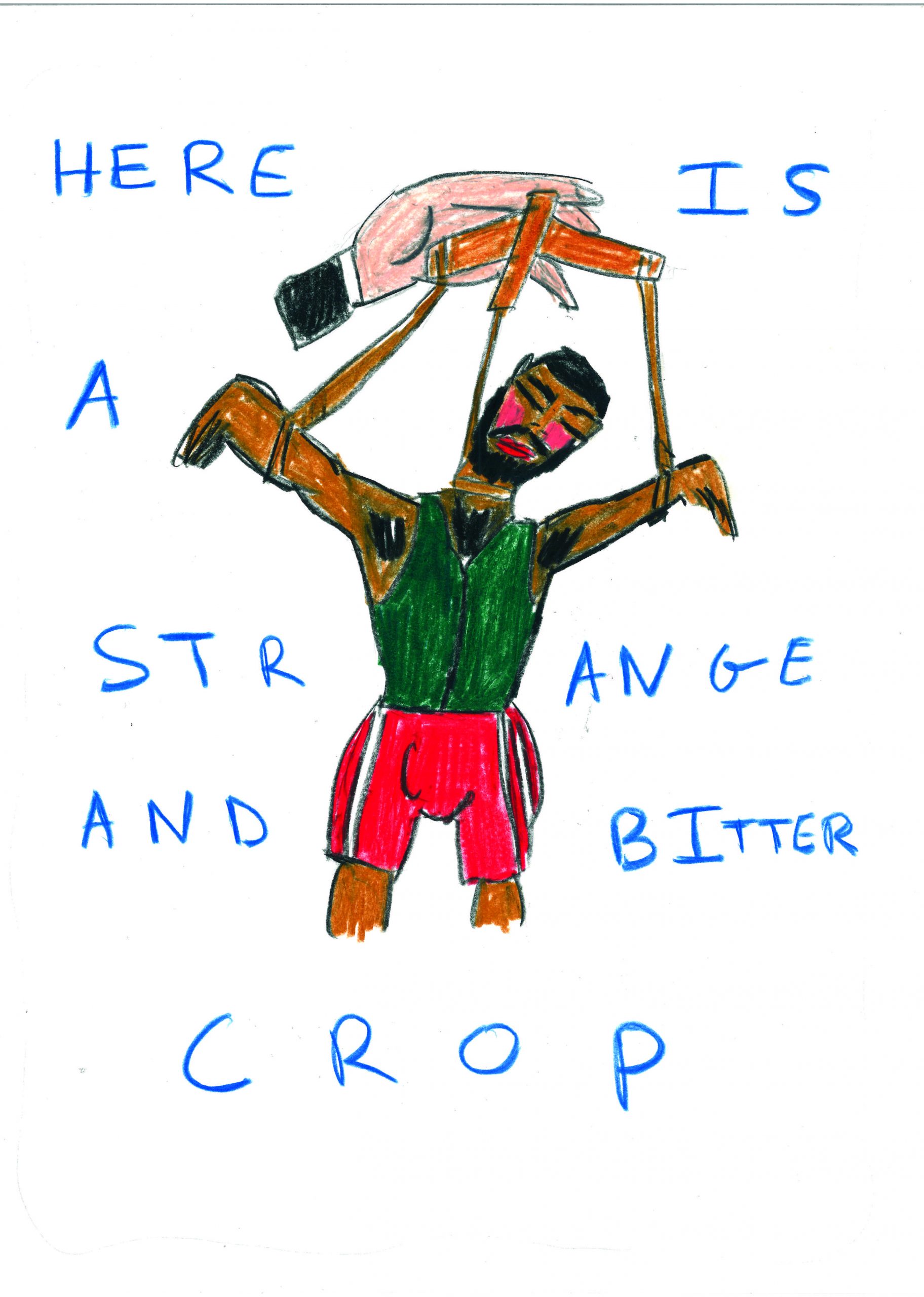

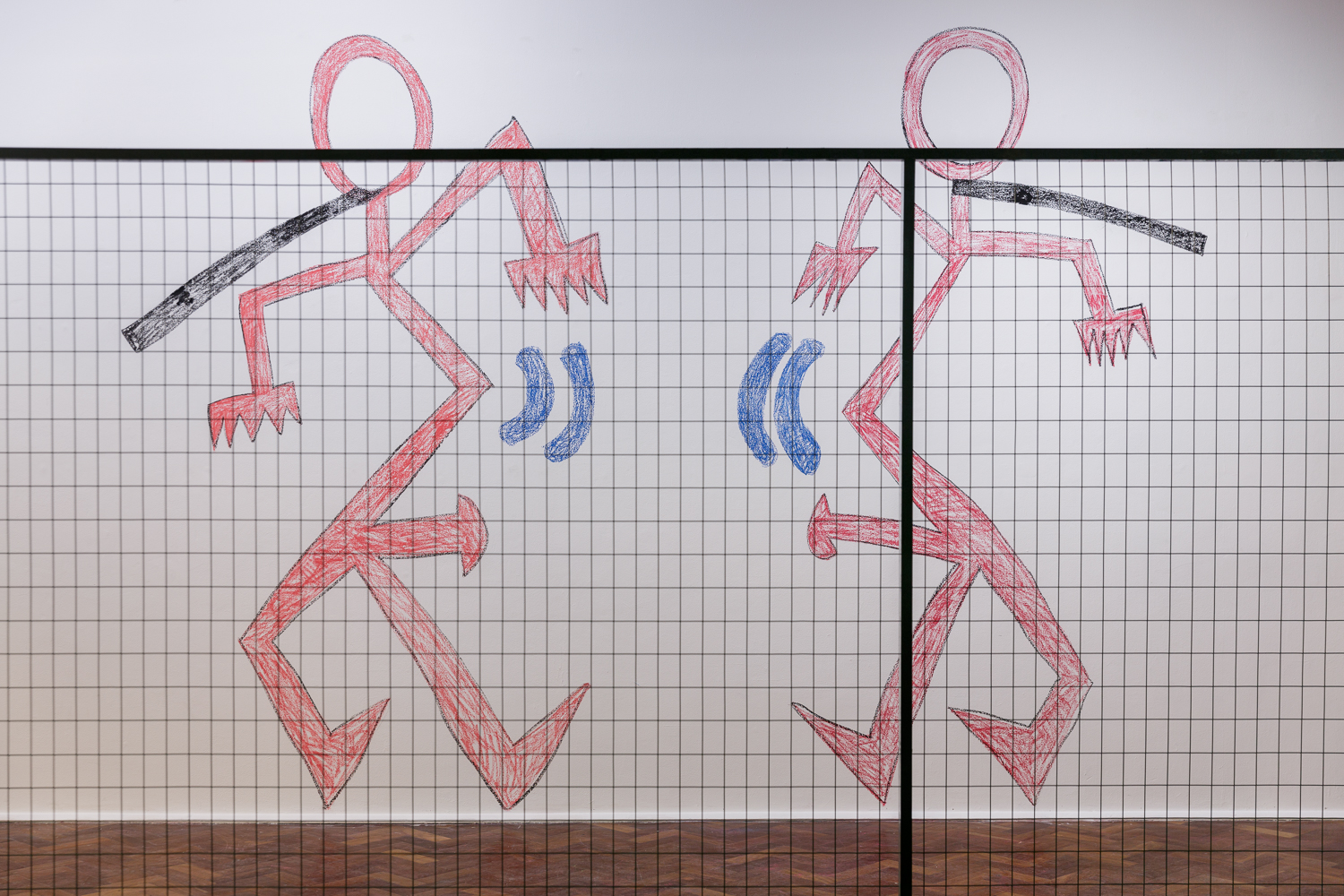

For the subject matter of his drawings, the artist has appropriated from gay male pornography, bringing together images of groups or pairs of black and brown men in various explicit sexual acts and linking them conceptually with two narratives — the harrowing song Strange Fruit, famously sung by the African American jazz singer Billie Holiday about the lynching of African Americans from the time of slavery into the 20th century, and the tragic story of the self-inflicted hanging, in 1998, of the popular London footballer, Justin Fashanu. The lynching metaphor is apparent in both the title of the exhibition, which is taken from the last line of Holiday’s song, as well as the title of the drawings. On a wall opposite to the Beautiful Fruit drawings is a mural depicting a series of figures reminiscent of Bruce Nauman’s Hanged Man (1985), but painted in a style half way between Nauman and Keith Haring. These figures make reference to the metaphor of the puppet and puppet master, an idea derived from a line quoted from a 1964 speech by Malcolm X in which the militant activist references African Americans as victims likened to the puppets of a racist society and the white power structure as the puppeteer.

In the 1990s, Fashanu was a popular sports star who is believed to have taken his own life by hanging himself. It is suspected that his demise was the result of external social pressures and his internal struggles to come to terms with his homosexuality. The black athlete’s tragic biography, along with Holiday’s own turbulent life and mournful version of the song involve a transmission of trauma that continues today in alternate forms such as police brutality and in the countless number of suicides of black and gay people in despair caused by various forms of social intimidation. In these instances, the victims are often subjected to and manipulated by a social system based on subjugation and domination.

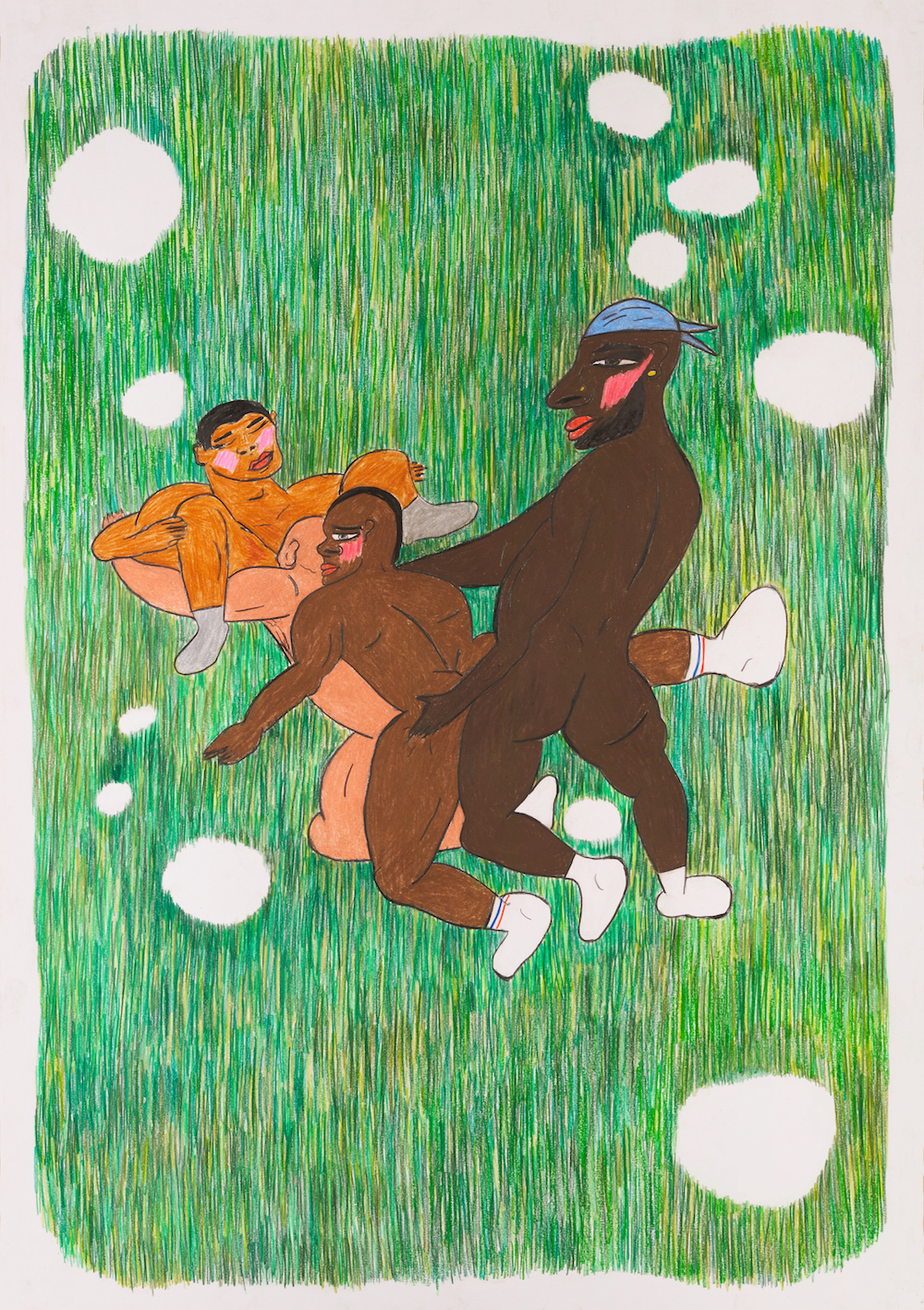

For this exhibition, Ababri draws from pressing contemporary themes and issues, transforming them into scenes that address the politics of race, masculinity, and homosexuality. Dark male bodies become tools of political reflection, of expressing desires, sexuality and history. The collective title of the six drawings in the exhibition, Beautiful Fruit, references the beautiful manly black bodies depicted set in metaphoric association with the violence of lynching that Holiday’s song evokes. This sequence of drawings builds and expands upon the artist’s ongoing Bedwork series, and focuses on gay men of colour as victims of rigid standards and expectations of what constitutes masculinity. Indeed, the majority of Ababri’s works are about the vulnerability and insecurity of masculinity and its mechanisms of domination that stifle or subordinate gay men. He is convinced that men need to find ways to free themselves from their socialised roles as men.

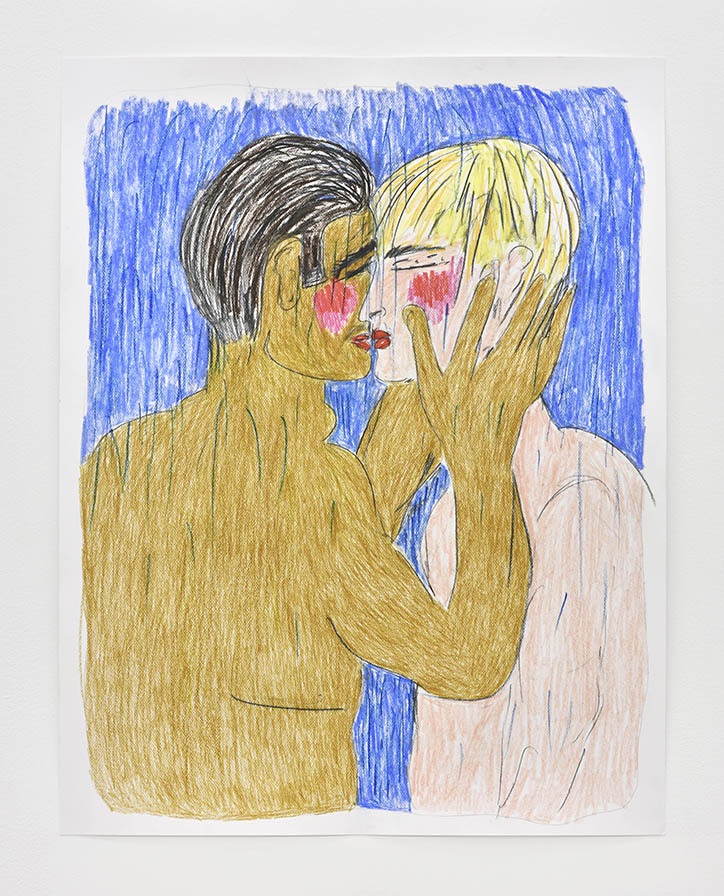

With Beautiful Fruit, the artist focuses on men of colour who have a virile disposition in terms of bodily appearance, but puts them in circumstances in which they engage in erotic acts that could be viewed as feminised. His brawny men are shown with pink cheeks that symbolize a body that loses representational control of itself and betrays the social game that such a virile physique implies. Pink cheeks on muscular bodies undermine the notion of masculinity and the game of patriarchal domination. Representing the masculine body in this way exposes the fragility of masculinity as a social construction.

Inspiration for Ababri’s drawings comes from a variety of sources such as photographs, films, archival imagery and magazines. For these images, the artist has used photographic extracts taken from pornographic films. His appropriation of gay pornography operates as a creative instrument for deconstructing ethnicity and masculinity. The lines between pornography and erotica are often blurred, subject to personal interpretation of what constitutes either obscenity or art. Such imagery has been and continues to be steadily vilified and attacked by social conservatives and religious fundamentalists who do not hesitate to exploit such imagery as an excuse to inflict dominance and modes of control over others. Ababri taps into the gay pornographic realm as an instrument of countering masculinity’s insecurities and efforts at violence toward and dominance over queers of colour.

Ababri’s own position as a marginalised Moroccan gay man living in France informs all aspects of his work. However, his notion of the autobiographical is less about the journalistic specifics of any particular individual, including himself, and is more in reference to the social structure that can coalesce into one’s identity as part of a marginalised group such as immigrants, gays, people of colour, colonials, etc. He uses his art to rethink his own and our relationship to the social and cultural inner-workings of masculinity, race, gender, art and art history. A key feature at the heart of his artistic practice involves the constant rethinking of harmful concepts that play a destructive role in the formation of an individual’s identity. In this regard, Ababri’s works engage a constellation of themes around hyper-masculinity, homophobia, sexual exoticism, dynamics of visibility and invisibility, and alternate expressions of erotic and racial/ethnic desire. These interests are pictorially put in conversation with each other in ways that are eye-opening, liberating, but also threatening for some. The brilliance of his work lies in its critical intersectionality. That is, he cherishes the interactions of multiple identities and scrutinizes how they work together to reference larger social concerns.

Homosexuality and the homoerotic carry political and social urgency tied to the artist’s unique drawing style. Ababri has remarked: “I draw men in a homoerotic universe where hierarchies are constantly questioned and criticised. Power play, the dominant and the non-dominant, authority — everything is called into question when we deal with sexuality and eroticization.” There is a marked poignancy in Ababri’s eroticising of politics and politicising of eroticism.

The artist’s concentration on drawing as a preferred medium is exploited as a radical break from all that he had been taught in art schools and in the normative French educational system. In the history of art, drawing has been sidelined as a preparatory process on the way to finished forms and compositions. At one point, Ababri made a conscious decision to integrate drawing as a means to engage his thought process in bringing together art and social justice. It is with drawing that the artist reflects on and attempts to integrate the forces between the dominator and the dominated. Drawing allows the artist to work in a way that takes the negative and the injurious in the system of domination and turn it around to empower and give voice to those who have been historically subordinated.

The public and private, the intimate and societal cross paths through displays of artistic performance that read as heartfelt and colourful protests against the mechanisms of social domination and oppression that has become all too normalised. The artist’s goal of appropriating from gay male pornography is not simply to shock, but to examine critically the sexuality of marginalised groups as a way to resist masculine dominance and oppressive social structures. These images of men engaged in sexual acts are hung at the same level and displayed on a wall painted with dark and light green stripes that are intended to connote doubly a football field and the cotton fields of a southern plantation. The former makes obvious reference to Fashanu while the latter theme transports us to the American deep South and its historical legacy of slavery and lynching as transgression against dark bodies. The overall theme resonates with the oppressiveness, domination, and violation of bodies to which Holiday mournfully refers in Strange Fruit. The football field and the cotton field become spaces for creative action and redolent of ideas about masculinity and social techniques of control.

In all formal and conceptual aspects of this exhibition the artist is focused on the heritage and triumph over dominance and control of individuals and whole communities discriminated against because of their sexuality, ethnic origin, or the colour of their skin. To reference Justin Fashanu, Billie Holiday, and Malcolm X is to not only comment on society at large, but the artist himself. Although Ababri’s works are universal in their meanings, they ultimately have particular resonance with his own identity as a Moroccan gay man — as a member of a marginalised community in France. To reference African Americans, to think about gays who have been persecuted throughout the world because of their homosexuality, is to display an irreverence toward harmful conformist structures of the status quo and to intervene creatively with art that acknowledges and yet conscientiously undermines hierarchies of dominance and control over others.

---

James Smalls is Professor of Art History and Theory, and Affiliate Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies and Africana Studies at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. His research and publications focus on the intersections of race, gender, and queer sexuality issues in 19th century European art and in the art and culture of the black diaspora. He is the author of Homosexuality in Art (Parkstone Press, 2003), and The Homoerotic Photography of Carl Van Vechten: Public Face, Private Thoughts (Temple University Press, 2006).

Soufiane Ababri: ♪ Here is a Strange and Bitter Crop ♪♪

Soufiane Ababri: The Making of ♪ Here is a Strange and Bitter Crop ♪♪

Opening night performance at Soufiane Ababri’s exhibition

Panel discussion: ‘Beautiful Fruit’: LGBTQI+ artists on challenging normativity

Photography workshop with Jessie McLaughlin

Reading group: ‘La Croisiere’ with Cédric Fauq